Those who know me better than in passing, also know that I am interested in abandoned places and their history. So, when visiting Freeport in Alcochete, I took the opportunity to take a quick look at the salinas and the abandoned site of what used to be the most important national centre for drying cod. Afterwards, I started reading.

The fishing

The consumption of cod (Gadus Morhua) has been part of the Portuguese diet since at least the Middle Ages, with treaties dating back to the fourteenth century, in which Portugal exchanged salt for cod with England.

The first records of Portuguese boats involved in cod fishing in Newfoundland, a region located on the western coast of Canada and where the large “banks” of this fish are found, “(…) immense underwater platforms, date back to the 16th century. the small depth where cod concentrates taking advantage of plankton, hake and squid (…)” (Garrido, 2010: 26)

Portugal was already an important market for this product at the time. Apparently, at that time more boats of Portuguese origin were involved in cod fishing than those from other nations, such as the English, Spanish or French.

According to Álvaro Garrido, “(…) the scarcity of bread resulting from crises in cereal production in the fields and, certainly, the action of religious prescriptions of fasting and abstinence, helped to establish in the Mediterranean and Christian world the centuries-old tradition of consumption of salted and dried cod (…)” (Garrido, 2010: 31,32)

The salting and drying process aims to eliminate a large percentage of water from the cod, thus neutralizing the action of enzymes and bacteria that would otherwise contribute to the deterioration of the product. By allowing the properties of cod to be preserved for an extended period of time, salting and drying cod made it possible to expand its consumption far beyond its territory of origin.

Cod meat has virtually no fat (0.3%) and is made up of more than 18 percent protein, an unusually high percentage, even in a fish. When cod is dried, more than 80 percent of its meat, which is water that has evaporated, becomes concentrated protein – almost 80 percent protein.

Kurlansky, 2000: 36

The progressive decline in control of the seas by the Iberian fleets, due to the rise of other imperial powers, such as the English, determined that until practically the nineteenth century there was no cod fishing with Portuguese crews. Dried salted cod continued to be widely consumed in our country, but its trade was now essentially controlled by the English.

Only from 1830 onward, when tax legislation suitable for Portuguese shipowners was drawn up, did the Portuguese fleet meet the conditions to develop, though still using English boats and crews. Its duration was, however, brief, which meant that the number of ships used in major work fluctuated according to the legislative changes that were made from then on, which were not always favorable to the industry. In 1896, to give you an idea, there were only 12 Portuguese sailboats used in cod fishing. (Moutinho, 1985)

In 1901, however, an important fiscal impulse was given to the development of the activity in a more sustainable way, establishing a tax of 12 réis per kilo of fish, when previously, new vessels that wanted to enter service dealt with 39 réis per kilo. As a result, in 1924 there were already 65 sailing ships fishing the banks of Newfoundland and with a greater tonnage compared to the beginning of the century. (Moutinho, 1985)

Following the financial crisis of 1890-1892, which culminated in the country’s bankruptcy, and the instability of the First Republic, aggravated by the First World War, the country faced periods of high inflation, currency devaluation, higher import prices, trade deficit and difficulties for the treasury in guaranteeing imports of essential goods. At many times, the Portuguese population, especially those belonging to the humbler classes, went through periods of food famine. It was the so-called subsistence crisis.

The problem was not that the cod did not arrive in the country. It did. The problem is that inflation and the weakness of the national currency made it expensive, jeopardizing the role that cod traditionally played as a complement to the Portuguese diet. Furthermore, Portuguese shipowners found themselves in a precarious situation and in the hands of exporting countries which flooded the Portuguese market, causing falling prices and thus putting into question the economic viability of national campaigns.

Putting things in perspective; while in 1911 cod from Portuguese crews represented 11% of national consumption, in 1930 it only satisfied 8% of that consumption, meaning an important outflow of foreign exchange from the country. The national supply of this product was, therefore, largely in the hands of foreign powers, who manipulated the market according to their convenience, jeopardizing the regular supply of cod to classes with fewer economic possibilities.

It is this framework, finally, that seems to be at the origin of the corporate and anti-liberal legislation that the Estado Novo designed for the cod sector, similar to what it adopted for the rice sector.

The Interventionist Policy of the Estado Novo

The philosophy behind this policy was based on strong state intervention in the market, making it possible to arbitrate the various interests in question: shipowners, fishermen, importers and, finally, consumers. The objective was to increase national cod production, which would make it possible to employ a vast national workforce (not only fishermen from all along the Portuguese coast but also, for example, shipbuilding workers) to increase shipowners’ profits, turning their activities sustainable, and ensure consumption at affordable prices for consumers.

To pursue these objectives, the Cod Trade Regulatory Commission was created in 1934, following the great depression of 1929, which plunged cod prices on international markets. The CRCB was the axis from which this entire economic sector was organized. One of its main tasks was to define, based on an estimate of consumption needs, the quantities of national and foreign cod that could be sold on the national market in annual terms.

In this way, Portuguese shipowners benefited, who, between 1934 and 1966, held, on average, 60% of the national market.

Seeking to contain tensions between shipowners and importers and impose the harmonization of their respective interests, the State guarantees the former the sale of captured fish and imposes on the latter its acquisition based on a minimum price fixed per season. This means that only “national cod” could be imported. This was the first to be distributed and consumed.

Garrido, 2010: 124

The remaining market would be supplied through imports of cod by Grémio from exporting countries that, through bilateral agreements, got access to Portuguese products at competitive prices, such as wine or preserves.

Importers then distributed the cod to stockists and these, in turn, to retailers. National and foreign cod were sold by importers at similar prices, thus seeking to safeguard consumers. Importers were then compensated, because of the difference between the price at which they purchased foreign cod and the price at which they could sell it, through the Compensation Fund, created in 1947 by the government in order to subsidize importers and thus control inflation.

In 1935, the Cod Fishing Vessel Shipowners’ Guild was created, which brought together in a corporation the owners of the vessels and cod dryers and whose revenues came from a fee charged to its members.

The money thus collected was destined, among other purposes, for a cooperative fund, instrumental in granting credit to shipowners for their fleet renewal plans, and for a social security fund, through which several fishing neighborhoods, as well as schools, canteens and health services. This social work guaranteed the minimum conditions for the existence of labor available to embark on cod campaigns every year.

In 1936, Mútua dos Navios Bacalhoeiros was founded. This was responsible for securing insurance contracts that covered the risk of ships and fishermen on board, a very useful institution given the considerable number of vessels that sank.

Finally, in 1938, the Cooperative of Cod Fishing Ship Owners was created. The purpose of this was to acquire all the materials necessary for cod campaigns from various suppliers, such as salt, fuel, lines and bait. The concentration of purchases in the cooperative made it possible to considerably lower the prices of these materials for shipowners.

The Crisis

The sustained growth of Portuguese cod fishing over the decades faced two major challenges. The first was the end of fishing freedom in the seas and the second was over-fishing.

Regarding the first, the convention that determined that the territorial sea of each country, the one over which it had sovereignty, existed since centuries past, extended only up to 3 nautical miles. Beyond that, the sea was free to access. However, from the Second World War onward, this concept was challenged, with some countries intending to increase their exclusive area of influence beyond 3 miles, which put into question the principle of the free sea and put Portugal’s access to the banks near Newfoundland and Greenland in jeopardy.

In 1958, the UN Convention on the Territorial Sea allowed countries to claim as their territorial sea an area up to 12 miles, by fixing the width of the contiguous zone of coastal countries up to those same 12 miles. Denmark, with sovereignty over Greenland’s fishing grounds, applied this principle, unilaterally, in 1963, establishing, however, a transitional period until 1973, from which the Portuguese benefited.

In 1970 it was Canada’s turn to extend its territorial sea from 3 to 12 miles. From the 1970s onward, and without access to large cod banks, the Portuguese industry entered a deep crisis.

The only place left to the Iberians was a corner of the great bank and the entire Flemish Cap, a historic cod fishery (…) in international waters. Both the Portuguese and the Spanish removed significant quantities from this area, until 1986, when Canada decided to deny foreign boats in the outer banks and the use of St. John’s to acquire supplies and make repairs.

Kurlansky, 2000: 172

Already since the end of the 1950s, however, the decline of the Portuguese fishing fleet had set in. This was due to the effects of over-fishing the existing cod stocks.

At this time, the capacity of the fleet was still growing, but the ships returned from the banks with their holds lightly loaded; on average they only carried 70-75% of their cargo capacity. This means that operating income was scarce and that there was an under-utilization of fishing capacity. Productivity per vessel showed very low numbers: it fell from index 144 in 1955 – the year of highest productivity – to index 95 in 1959, the year of greatest scarcity of fish in the North Atlantic fishing grounds. (Garrido, 2010: 150)

In the 1970 financial report, the scenario is already one of generalized crisis, attributable not only to the decrease in the catch rate but also to the difficult recruitment of trained labor, the increase in wages, as well as the cost of salt, fuel, insurance for fleets and the cost of repairs. (SNAB, 1970)

Regarding labor costs, it should be said that at a time of great emigration in Portugal, it was increasingly difficult to find people willing to work on the dories in a situation of true labor exploitation.

The 1971 and 1972 reports warn of the growth of areas prohibited for fishing due to the issue of new legislation for territorial waters. The 1973 report and accounts present a new complaint: “The restrictive measures that have been adopted with a view to reducing the depletion of fish stocks inevitably affect the productivity of vessels”. (SNAB, 1973: 6) SNAB also continues to complain about the expansion of exclusion zones.

The 1974 and 1975 reports continue along the same lines of crisis, with abundant complaints about the decline in stocks, the rise in costs for equipping ships, and the expansion of exclusive zones in coastal countries.

A reflection of this crisis scenario is a reduction of 50% in fish catches, between 1967 and 1973, from 260 thousand tons to 130 thousand tons. (Moutinho, 1985)

In addition to all these problems, the frozen fish market was growing, where exporting countries now diverted a large part of the production, which left the market even more impoverished and hampered national supply.

Price control now became an obstacle, particularly for national shipowners, with a volume of fishing insufficient to cover operating costs. In this context, the Supply Fund, through which the prices of foreign cod were subsidized to the consumer, but whose revenues were obtained through the taxation of national cod, now increasingly small, reached an unsustainable situation, with serious problems for the treasury, leaving those responsible at the time no other option than to liberalize prices and abolish restrictions on imports.

In 1967, finally, the liberalization of imports and prices was decreed, putting an end to the political and institutional edifice that had presided over the cod sector since the 1930s. With the cod “banks” closed to Portuguese shipowners, the Liberalization of imports and prices was the only measure capable of guaranteeing the country’s supply of this fish. The world of free access to the seas and intensive use of labor on which the premise of the development of Portuguese industry was based had ended and, as a consequence, so had the political edifice that had been erected for its protection.

Back to Alcochete

Historically, the cod curing process began in bacalhoeiros (cod fishing ships), where it was immediately salted. Upon reaching land, the fish was washed to remove all the salt and dried to dehydrate it. Cod drying was done outdoors in the Algarve, South Bank of the Tagus, Setúbal, Figueira da Foz, Aveiro and Viana do Castelo. It was generally a job done by women.

With an area of 360 hectares, the Salinas do Samouco in Alcochete were, between the 1930s and 1970s, the main salt production center in the Lisbon region. From here, the salt was shipped in boats for salting cod, in distant Newfoundland, or for warehouses, in Cais do Sodré, to be consumed in the capital.

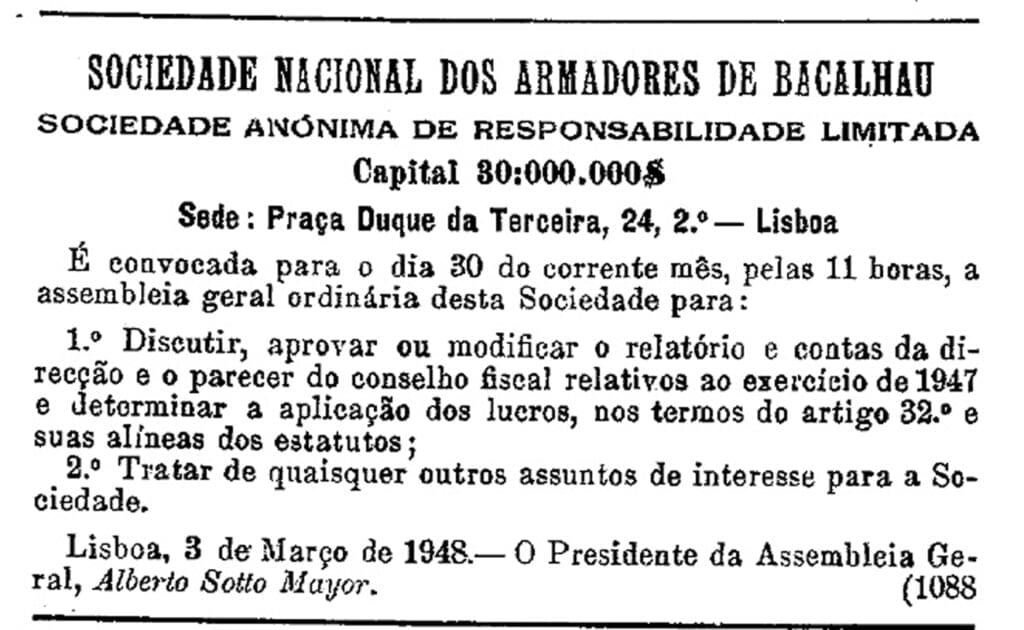

The Sociedade Nacional dos Armadores de Bacalhau was created by public deed of May 8, 1940, with a share capital of 100,000,000 escudos and having as shareholders shipping companies and other entities in the sector, such as the Grémio dos Armadores de Navios de Pesca do Bacalhau and Mútua dos Navios Bacalhoeiros.

The story of the cod drying in Alcochete begins in 1941. However, and this I find rather strange, only in 1951 the first company opened its doors. In the following decade and a half, Alcochete became the largest national centre for drying and preparing cod. At certain times, on the town’s pier and offshore there were several cod boats anchored. They unloaded the catch from Canadian waters and loaded salt for the following catch. The largest luggers could not reach these piers, so loading and unloading was carried out by frigates, who then moved the catch further up the river.

In 1942, a program of renovation of the cod-fishing fleet was implemented, which resulted in an increase from 34 vessels (1934) to 77 (1958). Thus, in just a few decades more than 80% of the codfish consumption in Portugal was accounted for by domestic production.

So vital was the Portuguese cod-fishing fleet, that the men who volunteered to work in it were exempted from compulsory military service. Cod fishermen were elevated to the rank of homeland heroes, the rightful heirs to the sailors who had carried Portugal’s name overseas.

The Sociedade Nacional de Armadores de Bacalhau, one of the three cod drying and preparation factories that existed in Alcochete and of which only the building remains today, was located at the entrance to this complex.

1974 was the last year in which a fleet of cod ships left for Newfoundland, which coincides with the fall of the dictatorship in Portugal. However, nowadays we still love cod and it is said that in Portugal there are a thousand-and-one different ways to prepare it.

When looking for information about this specific place, I can’t help thinking that a lot has been done to create the notion that the bankruptcy was caused by mainly situations outside the owners’ control, like the decline of fishing grounds and more restrictive international legislation. However, when reading between the lines, there are enough facts that hint towards mismanagement on several fronts. Why did it take from 1941 till 1951, for instance, to establish the first drying tunnels?

As Fonseca Bastos wrote in 2008: “The justification for the sale at a lower price than usual is stated in the minutes and the reasons seem reasonable, given the difficulties in the development of the municipality at the time, but among the oldest Alcochetans, some questions still persist today.”

A few facts:

Stock Status Update of Atlantic Cod:

- In 2022, the total catch of Atlantic Cod in NAFO Divisions 4X5Y was 630 metric tonnes, which is below the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) of 825 metric tonnes;

- The catch distribution is primarily from the Scotian Shelf, accounting for 70% of the total fishery removals, while the Bay of Fundy contributes around 30%.

Global Cod Fisheries:

- The European Union (EU) catch in 2022 was approximately 3.4 million tonnes of live weight, a continuation of the downward trend;

- The majority of the EU catch is taken in the Atlantic, Northeast area.

Cod Consumption:

- In Spain, the sales volume of cod has been steadily decreasing from 2008 to 2018, with a significant drop in 2018.

Regional Cod Fisheries:

- The North-East Arctic Cod stock is the world’s largest population of cod and is found in the Barents Sea area. The biomass of this stock was estimated to be at an all-time high in 2012;

- The North Sea cod stock is primarily fished by European Union member states and Norway, with catch quotas repeatedly reduced in the 1980s and 1990s due to concerns about over-fishing.

Portuguese Cod Consumption:

- The Portuguese are responsible for consuming around 20% of the world’s catch;

- 95% of the cod consumed in Portugal is dried and salted;

- The drying and salting of cod in Portugal primarily takes place in Norway;

- The majority of the cod consumed in Portugal is imported from Norway, known as “Bacalhau da Noruega”.

Sources:

- Pedro Rêgo: História da pesca e do consumo de bacalhau em Portugal – breve introdução

- Visitisboa: História do Bacalhau

- RTP: Faina maior pesca bacalhau

- Álvaro Garrido: O bacalhau é, de longe, o primeiro símbolo da identidade nacional

- Fonseca Bastos: Subsídio para a história das secas do bacalhau

- Lara Silva: Understanding the Portuguese obsession with cod

- Murthy A, Galli A, Madeira C, Moreno Pires S: Consumer Attitudes towards Fish and Seafood in Portugal: Opportunities for Footprint Reduction